Lunar samples retrieved by China’s Chang’e-5 mission have provided new clues that may hold the key to understanding the habitability and development of other planets.

The magnetic field lasted well into its middle years far beyond when it was believed to have vanished.

Researchers discovered that the Moon’s magnetic field measured between 2 to 4 microteslas around two billion years ago, which is less than 10 percent of the Earth’s present-day surface magnetic field. The findings were published in the Science Advances journal on Thursday.

Ross Mitchell, a co-author on the paper from the Institute of Geology and Geophysics in Beijing, stated that some thought the moon’s magnetic field had probably disappeared by then, but their research indicated it was “at least still lingering”.

Our brand-new platform offering a meticulously selected library of exhibits, comprehensive explanations, frequently asked questions, in-depth analyses, and informative graphics, all crafted by our team of highly accomplished experts.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology planetary scientist Benjamin Weiss suggests the moon’s weak but extended magnetic field could have been a result of enduring interior processes, including core crystallization or interactions between the core and the mantle.

These processes would have kept the moon’s magnetic device, known as the lunar dynamo, operational for billions of years.

“The moon goddess’s elixir appears to be effective,” Weiss noted in a review article summarizing the results. He was referring to the Chang’e missions, which are so named because they are inspired by the legend of the goddess of the moon, who fled to the moon after stealing an elixir granting her eternal life.

According to the study’s results, a persistent magnetic field around the moon can have protected its surface from solar radiation and helped keep volatile substances, such as water, in place.

Knowing the moon’s magnetic history in detail is crucial to understanding the potential for life and the process of evolution on other planets.

The Apollo missions suggested its presence approximately over three billion years ago, with magnetic field strengths comparable to the present field, which spans from 25 to 65 microteslas.

.

It is still uncertain for how long the lunar dynamo functioned.

Analyzing these American Apollo samples proved to be difficult due to their relatively older age, their large iron grains which were causing a poor preservation of magnetic signals and other constraining factors, Weiss observed.

missions five decades ago.

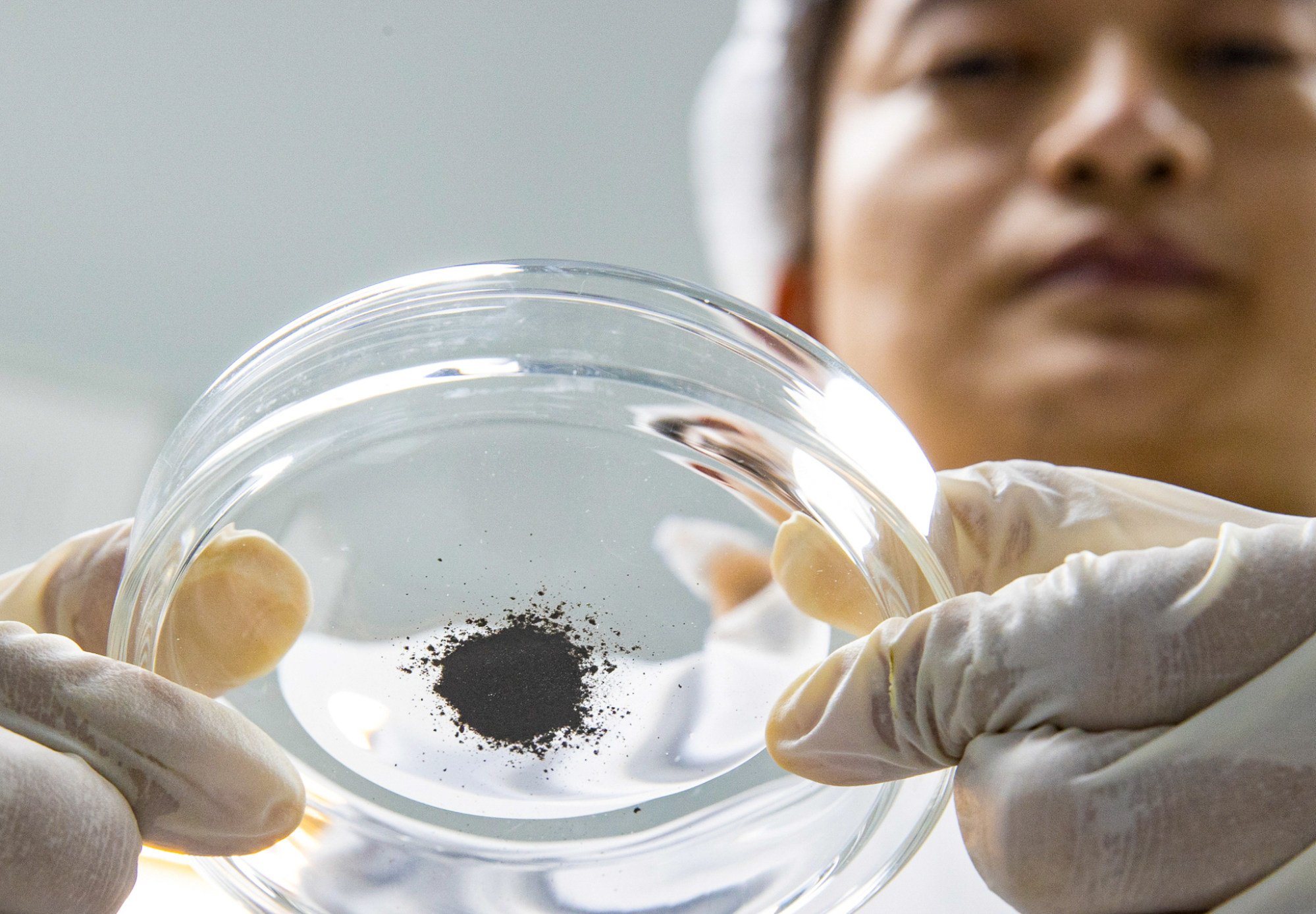

In conducting this research, the scientists identified nine small pieces of basalt – each measuring 3-8 millimeters in diameter and weighing under 0.3 grams.

These fragments acted like magnetic recorders, preserving the magnetic field present when the rocks formed billions of years ago. The researchers then extracted the ancient magnetic signals using highly sensitive laboratory techniques.

“When it comes to magnetism, small sample sizes mean weak signals, which require laborious and meticulous laboratory work,” said lead author Cai Shuhui, a colleague of Mitchell’s at the Institute of Geology and Geophysics.

They were “just good enough,” she said.

The magnetic field strength of two to four microteslas was notably weaker in comparison to the significantly stronger fields present in the early history of the moon, which reached tens of microteslas.

Magnetic field is extremely powerful well beyond prior estimates.

“A magnetic field generated in the moon’s core implies that its deep interior was still hot and active enough to explain the puzzling late volcanism revealed by the young Chang’e-5 samples,” Mitchell stated.

More Articles from SCMP

Hong Kong-Zhuhai-Macau Bridge Half Marathon: “Citizen Runner” Among Top Athletes Competing

Mourners Assemble at Hong Kong Mosque for Funeral Rites of Car Crash Victims

Silence on the sets: China’s film industry struggles for relevance in the evolving media scene

Beijing considers long-awaited salary hike for government employees, but its economic impact remains uncertain.

This article was first published in the South China Morning Post (www.scmp.com), the primary news source for reporting on China and the Asia region.

Copyrights (c) 2025, South China Morning Post Publishers Ltd. All rights reserved.