A journey into Karnataka’s colonial past explores four refurbished railway stations on the Bengaluru – Kolar railway route.

The name of Bengaluru’s main railway station comes from an 19th century military leader from a town about 300 miles northwest of the Indian city, who rebelled against the British and was put to death for it.

Standing beneath the awning of the Krantiveera Sangolli Rayanna railway station in Bengaluru on a chilly Saturday morning, recalling his name offers a fitting beginning to a journey back in time, as the goal is to delve into the city’s colonial railway heritage.

A major juncture, the station is always bustling. But platform six is relatively tranquil as I join a small group that has gathered for a day-long train journey, along with a walk, hosted by the Bengaluru chapter of the Indian National Trust for Art and Cultural Heritage (INTACH), an NGO with UN consultative status that works to safeguard India’s natural and cultural heritage through volunteer-run chapters.

Our latest platform features a collection of informative content, including in-depth explanations, frequently asked questions, technical analyses, and visual representations, all provided by our highly-acclaimed team.

We board the Bengaluru-Kolar Special, headed to four British-constructed stations that fell into disrepair, but were meticulously restored by Intach.

As the train accelerates its pace, it runs through neighborhoods beginning their day in anticipation of the weekend; however, the urban landscape soon gives way to a broader expanse of agricultural land: fields of oscillating marigold and chrysanthemum flowers, coconut trees, orchards, and grapevines.

BMTC Convenor Meera Iyer takes the time to provide a brief overview of the history of Bengaluru and establishes the context for the line’s creation. (The organization occasionally offers public tours and private group tours.)

According to Iyer, the 81km line’s main section was built as a narrow gauge in 1915 for passenger and goods transportation on a highly active commercial route. It was later upgraded to broad gauge and extended to both Bengaluru and Kolar. Many of the line’s stations date back to this period, but sadly, they have been largely neglected.

Four years ago, Intach began a campaign to restore four stations in partnership with South Western Railway, the responsible governing authority, and in collaboration with local communities and business establishments. We are soon to experience the outcomes.

The platform stop is brief initially but we’re allowed just enough time to notice it’s different from the other stations so far. A stone exterior and a pitched roof suggest its origins.

Iyer displays photos from the restoration process in the coach.

Devanahalli and Avatihalli stations resemble Dodjala in build. All are modest in scale, with a small hall serving as a waiting area, storage section, and ticket booth. A blend of colonial and local architectural styles is discernible. Thick, solid stone walls provide a backdrop to gabled roofs topped with Mangalore tiles, a baked-clay type introduced by German missionaries in 1860. These tiles are laid on wooden beams held in place by metal bars, with overhangs supported by stone pillars.

A notable distinguishing feature is the monkey top, which is a common component on Bengaluru’s colonial architecture: spiky elements protruding from pitched roofs above windows and other areas, likely intended to discourage monkeys.

The last stop is the best one.

It is at Nandi Halt that passengers disembark for a historic temple complex or a hill station which was previously used as a summer retreat by British officers.

We exit the train and enter the village that bears its name in the foothills of Nandi. At its center is the Bhoganandishwara complex, a display of Dravidian temple architecture.

This ancient structure features a variety of buildings, including intricate temples built in a pyramidal style common to South India, performance areas, banqueting halls for weddings, and a massive public water reservoir. Virtually every surface of these buildings is richly decorated with fine engravings, decorative embellishments, sculptures of dancing nymphs, and detailed carvings portraying stories from the Indian epics of Ramayana and Mahabharata.

The village of Nandi encircles the temple complex, with narrow streets and alleys lined with closely situated houses. A constant hum is generated by machinery and textile equipment used in the production of silk yarn, with various activities centered around it.

It is a common occurrence to find households in this region that have been involved in the production of silk for several generations, with some dating their heritage back to the time of Tipu Sultan, a late-18th-century leader who advocated for sericulture, or the cultivation of silkworms for silk, and led a formidable campaign against the British, nearly defeating them.

It is this type of history and cultural heritage that Intach aims to record and showcase in exhibitions at the revamped railway stations.

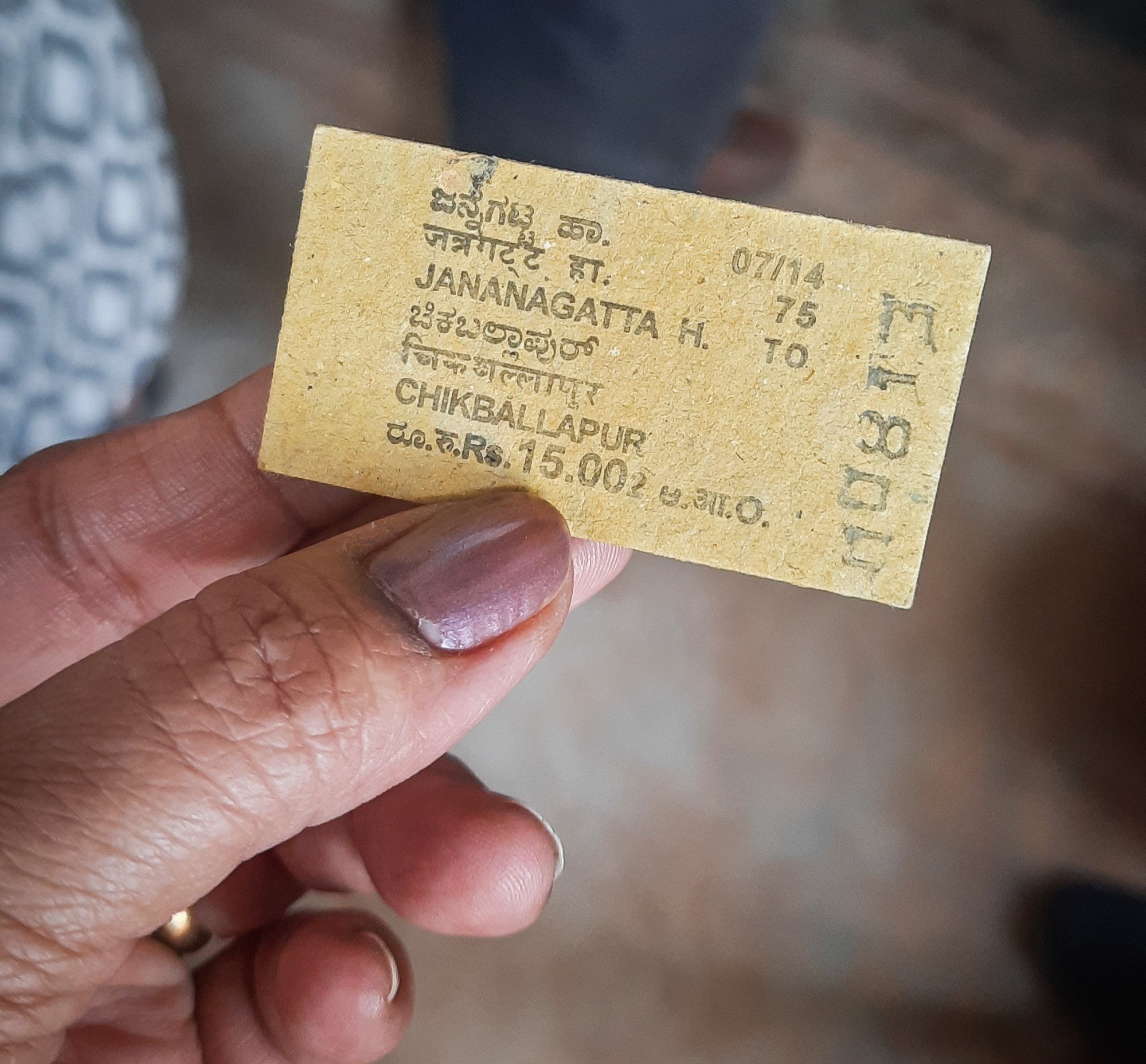

We head back to the Nandi Halt station, which is a larger building than the other three restored stations, featuring a rectangular design with an arched entrance passage flanked by what are likely to be old waiting rooms. The ticket counter is discreetly located in a corner of the building and issues something of a rarity these days: “Edmondson” rail tickets, which are traditional, pre-printed tickets named after their inventor, Thomas Edmondson (1792-1851), a renowned figure from Manchester, England.

Iyer and her team guide us through the station building, navigating around the limited number of regular train passengers, while explaining the restoration process, which involved acquiring wood for the rafters and efforts to replicate the original mortar used in the construction.

We have maintained the original building materials as much as possible, such as the stones and Mangalore tiles,” says Iyer. “There are only slight modifications and changes were made only where they were necessary to ensure the structure’s stability.

As we head back down the line, Intach co-convenor Aravind Chandramohan outlines a few more of the NGO’s plans: “Dodjala station has been transformed into a gallery space featuring some railway heritage photos on display. We are planning to establish a silk museum at Avatihalli station.”

A historical interpretation centre is planned for Devanahalli, given its proximity to a nearby fort and its designation as Tipu’s birthplace, as well as plans for Bengaluru’s very first railway museum at Nandi Halt.

As the train rumbles back into Krantiveera Sangolli Rayanna, it seems that Intach’s plans incorporate those spaces in a meaningful way.

More Articles from SCMP

Danny Shum Chiu-hin takes the lead in the championship with the January Cup triumph, making him a four-time winner at Happy Valley.

Hong Kong entrepreneur Allan Zeman’s Lan Kwai Fong Group plans major entertainment complex in Xi’an.

China’s military has improved air supply for its troops stationed at the border with India in the Himalayas.

Chinese actress accuses talent agency of verbal and physical mistreatment after failure to secure acting roles

This article was originally published on the South China Morning Post (www.scmp.com), a leading news source covering China and Asia news.

Copyright (C) 2025. South China Morning Post Publishers Limited. All rights reserved.