Norway aimed to achieve the target of electric cars replacing all new car sales by 2025, a full 10 years ahead of its European counterparts. Subsidies and incentives have largely enabled the Nordic country to reach this ambitious goal, so what insights can other nations glean from its success?

Norway is serving as a striking example of the transition to electric vehicles (EVs). Latest official government data indicates that nearly nine out of every 10 cars sold were electric in the previous year.

In 2023, the worldwide adoption rate of electric vehicles was at 18%, the latest available data shows, based on information from the International Energy Agency.

The Nordic nation has made a significant pledge to address climate change, fueled by bold government initiatives, comprehensive infrastructure, and a populace that is highly receptive to environmental efforts.

Norway aspires for all passenger cars sold to be zero-emission vehicles by the end of the current year, a full decade prior to the European Union’s target deadline.

In regions such as Puerto Rico or Singapore, the small population size creates a unique business environment that is relatively easy to navigate, with minimal bureaucratic hurdles to overcome.

Norway’s wealth and size have certainly contributed to its impressive success with electric vehicles. With a population of approximately 5.5 million, it is one of the wealthiest countries in the world, primarily due to its vast oil reserves – the largest in Europe, after Russia. Nevertheless, these factors alone don’t entirely account for the country’s remarkable progress in this area.

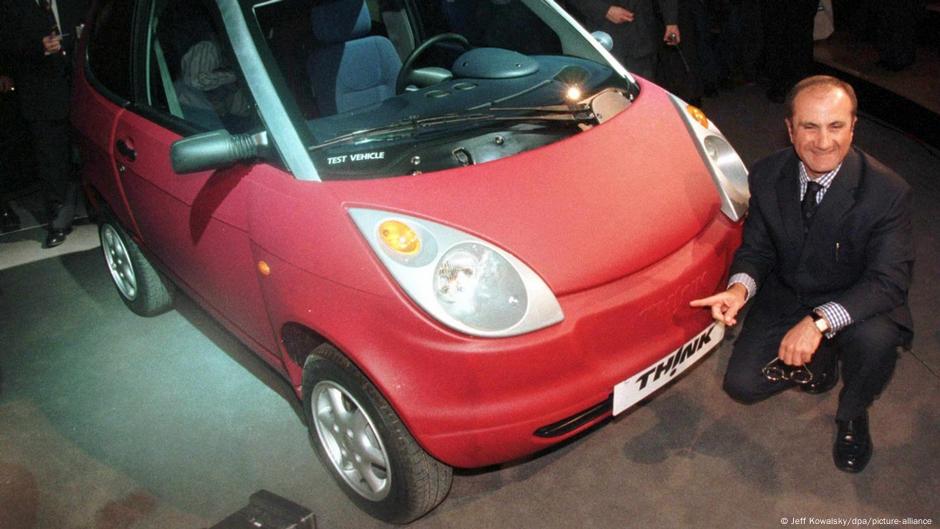

Robbie Andrew, a senior researcher at the CICERO Center for International Climate Research, a research center based in Oslo, believes Norway’s extensive investment in domestic electric vehicle development over several decades was crucially important.

and Volkswagen.

Tax benefits and the ease of mobility helped.

Favourable government policies have undoubtedly facilitated a smooth transition to electric vehicles. Norway imposes neither Value-added tax (VAT) nor import duties on EVs, which can account for between a third and nearly half of the cost of a new car.

Electric vehicles were also exempt from toll road charges and parking fees. They were also allowed to use bus lanes in and around the capital, Oslo.

Higher-income households reaped the most rewards from the tax deductions, and the newly acquired electric vehicle was frequently a second car for the family.

Reaching nearly 2025 adoption target, the authorities have removed certain incentives for electric vehicles. Value-added tax is now applied partially to high-end and luxury EVs, with a price tag exceeding 500,000 kroner ($44,200, €42,500). Meanwhile, individuals from low-income backgrounds continue to benefit from various remaining incentives and decreasing EV cost.

Bjørne Grimsrud, director of the Oslo-based transportation research center TOI, believes that government incentives have been “very costly” but viable, considering Norway’s wealth and its goal of being climate-neutral by 2050.

Annually, the government’s revenue used to be around 75 billion kroner, split between taxes and car tolls. Now, the income from these sources has taken a significant drop, to a halved amount.

Electric vehicle adoption slowed in other regions due to subsidy reductions.

Other countries, including Germany, are being criticized for not achieving their climate-mitigation targets by reducing subsidies for new electric vehicles well ahead of schedule. In a recent announcement, Germany’s transport authority stated that the number of electric vehicles registered in 2024 decreased by 27.4% compared to the previous year, having the largest auto market in Europe.

the company aims to meet its goal of having 15 million electric vehicles on the road by 2030.

Norway spearheaded the installation of home charging stations.

Norway benefits greatly from its power grid, which is one of the cleanest and most reliable in the world. More than 90% of Norway’s electricity is generated by hydropower, typically resulting in a surplus of energy which makes it feasible for EV charging at home.

“While charging facilities are scarce elsewhere in Europe, most Norwegians can charge their electric vehicles at home,” Grimsrud said.

A 2022 study by the Norwegian Electric Vehicle Association found that approximately three-quarters of electric vehicle owners reside in detached houses, which allows for easier installation of home charging units. An investigation conducted by the London-based consulting firm LCP discovered that 82% of electric vehicles in Norway are recharged at home, although this percentage is lower in urban regions.

Noel suggested that other countries could benefit from “considering less expensive and more conspicuous ways to integrate EVs into society” instead of emphasizing the construction of faster, public charging facilities, often referred to as Level 2 and 3.

US President unlikely to replicate Norway’s success with school voucher programs.

As they await President Trump’s return to the White House, many Americans are worried he may shift from the Biden administration’s policies favoring widespread adoption of electric vehicles, inspired by Norway’s progress in this area.

The incoming Republican president has promised to cancel federal tax credits up to $7,500 (€7,230) for electric vehicle (EV) purchases, plus impose new tariffs on foreign automakers, which could drive up prices. Additionally, several US states plan to reduce their own EV incentives. This move comes despite a forecast by Cox Automotive that only 8% of Americans would adopt EVs last year.

The US has also witnessed a decrease in electric vehicle sales recently, primarily due to affordability issues and limited charging infrastructure availability. Last week, Tesla reported its first sales downturn in more than a decade.

Citing the potential reversal of EV policies under the Trump administration, Noel mentioned that it’s no surprise that countries heavily investing in EV policy see the most benefits from their efforts.

Some countries may struggle to replicate Norway’s success, which might be due to a lack of strong and clear policies supported by political willpower.

Edited by: Uwe Hessler

Author: Nik Martin