-

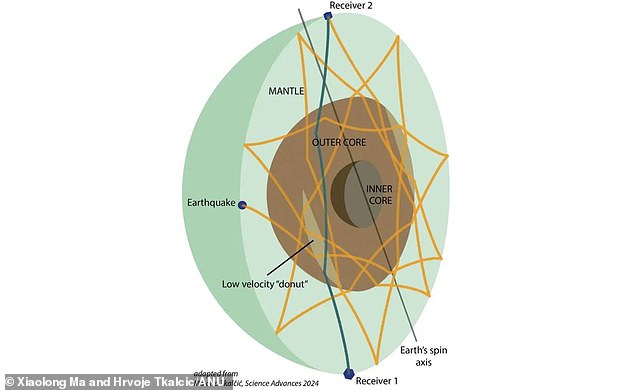

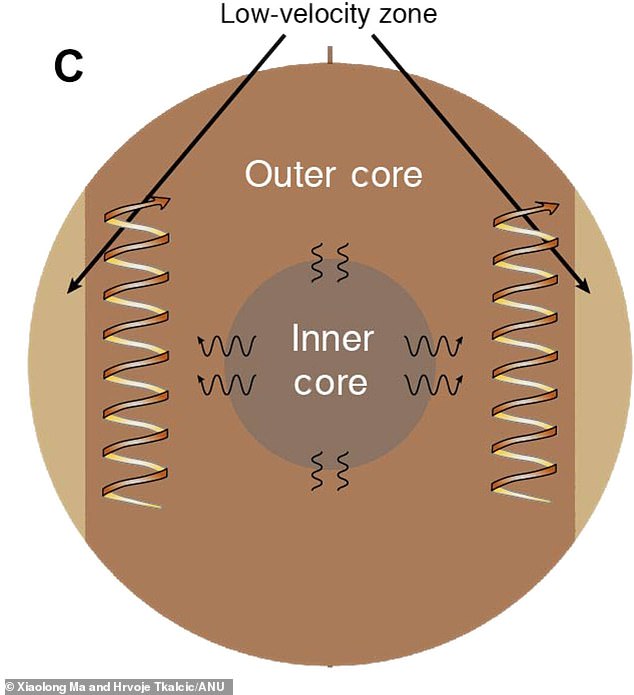

Scientists have identified a ring-shaped area near the top of the Earth’s outer core.

-

This lighter-colored area helps mix the liquid metal, producing the magnetic field.

Researchers have discovered a massive, ring-shaped formation hidden thousands of miles beneath the Earth’s surface.

To observe the Earth’s enigmatic molten nucleus closely.

By tracking the path of these waves across the planet, the researchers discovered an area a couple of hundred kilometres deep where they traveled two percent slower than usual.

The donut-shaped structure extends parallel to the equator, encircling the edge of the liquid outer core as a ring, and may be accountable for generating our Earth’s shielding magnetic field.

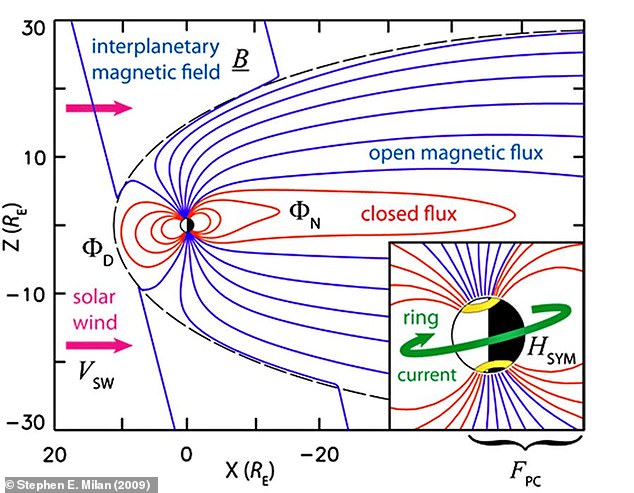

Lead author Professor Hrvoje Tkalčić comments: ‘The magnetic field is an essential element we need to support life on the surface of our planet.’

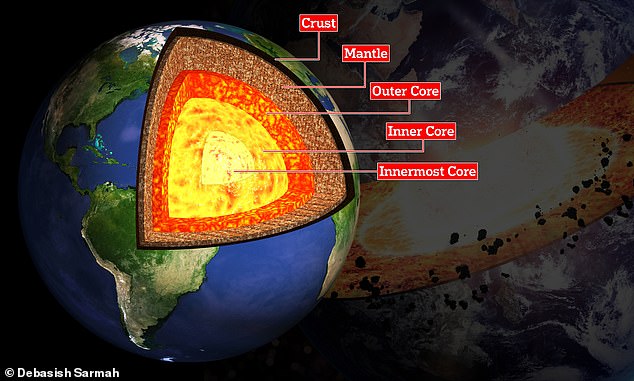

The surface layer, the partially molten mantle, a liquid metal outer core, and a solid metal inner core.

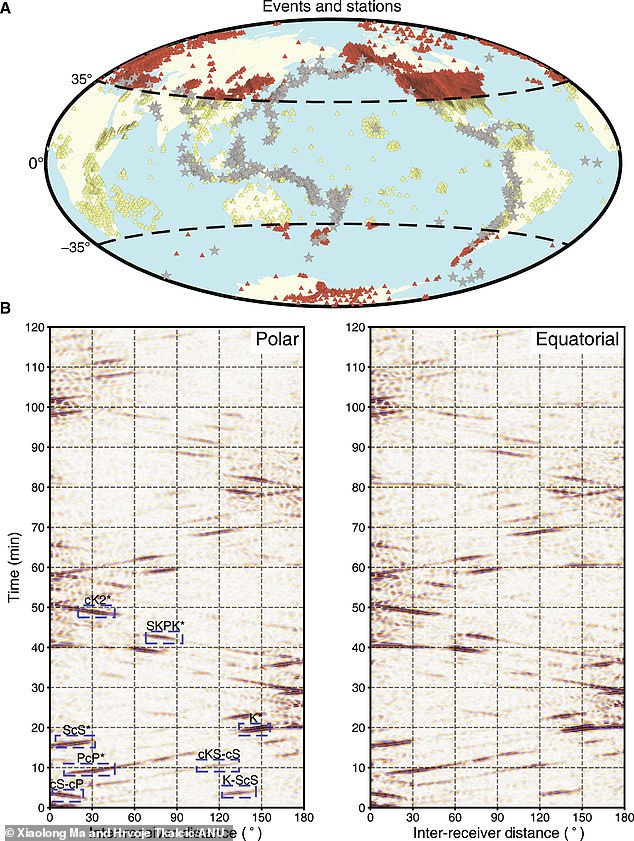

When the movement of tectonic plates in the Earth’s crust results in earthquakes, these cause vibrations that travel outward through all other layers of the planet.

Researchers can see how the waves spread and can make forecasts about the ocean conditions beneath the surface.

Researchers typically focus on the large, intense wavefronts that move globally within the first hour or so after an earthquake.

However, Professor Tkalčić and his co-author Dr. Xiaolong Ma were able to recognize this structure by analyzing the faint marks left behind by waves long after the initial quake.

This approach uncovered the surprising fact that seismic waves traveling near the polar regions were moving at a speedier rate than those closer to the equator.

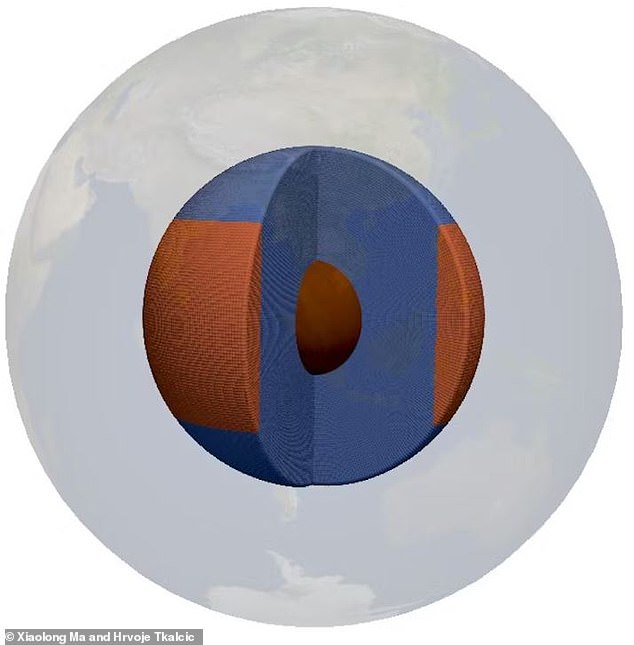

By comparing their results to different models of the Earth’s interior, Professor Tkalčić and Dr. Ma found that their findings were best explained by the presence of a massive subterranean “torus,” or ring-shaped, region.

They forecast that this feature is only present at low latitudes and extends parallel to the equator near the top of the outer core where the liquid portion merges with the mantle.

“We do not have the precise thickness of the doughnut-shaped structure, but we inferred that it extends around a few hundred kilometers beneath the core-mantle boundary,” Professor Tkalčić says.

This region plays a critical role, and their discovery could have significant implications for the study of life on Earth and other planets.

The Earth’s outer core has a diameter of approximately 2,160 miles (3,480 kilometers), which is slightly greater than that of Mars.

The layer is primarily composed of glowing hot nickel and iron, and is driven by convection currents and the Earth’s rotation into massive, twisting columns of fluid that extend vertically, with a predominantly north-south alignment, resembling colossal, rotating spirals.

It is the swirling currents of these liquid metals that act like a dynamo, powering the Earth’s magnetic field.

As this donut-shaped region has risen to the surface of the liquid outer core, it implies that it could be abundant in lighter elements such as silicon, sulfur, oxygen, hydrogen, or carbon.

Professor Tkalčić says: “Our findings are fascinating because this slow movement within the liquid core indicates a high concentration of light chemical elements in these areas that would cause seismic waves to slow down.”

‘These lightweight elements, along with temperature variations, assist in mixing matter within the outer core.’

Had there been no iron agitation to stoke the planet’s internal dynamo, the Earth’s magnetic field may not have taken shape.

From the sun, whose ultraviolet rays can cause damage to the DNA of living organisms.

This doughnut-shaped area, therefore, could be a crucial component in explaining how life emerged on Earth and what we should seek out in habitable planets across the universe.

Dr. Tkalčić concludes: ‘Our research results could contribute to further investigation of the magnetic field on Earth and other planets, stimulating more study in this area.’

Read more