This text does not need to be paraphrased.

The town is home to nearly 25,000 people. However, he has also worked on dozens of redevelopment projects in other estates, trying to transform generic apartment buildings into unique and inviting structures.

His assessment is that they are quite dull, states Chan, the founder of interior design firm Hintegro. “I would say they are quite boring,” declares “There are many constraints when I design an interior for large estates,” he notes, “You don’t have the freedom or flexibility to eliminate anything.”

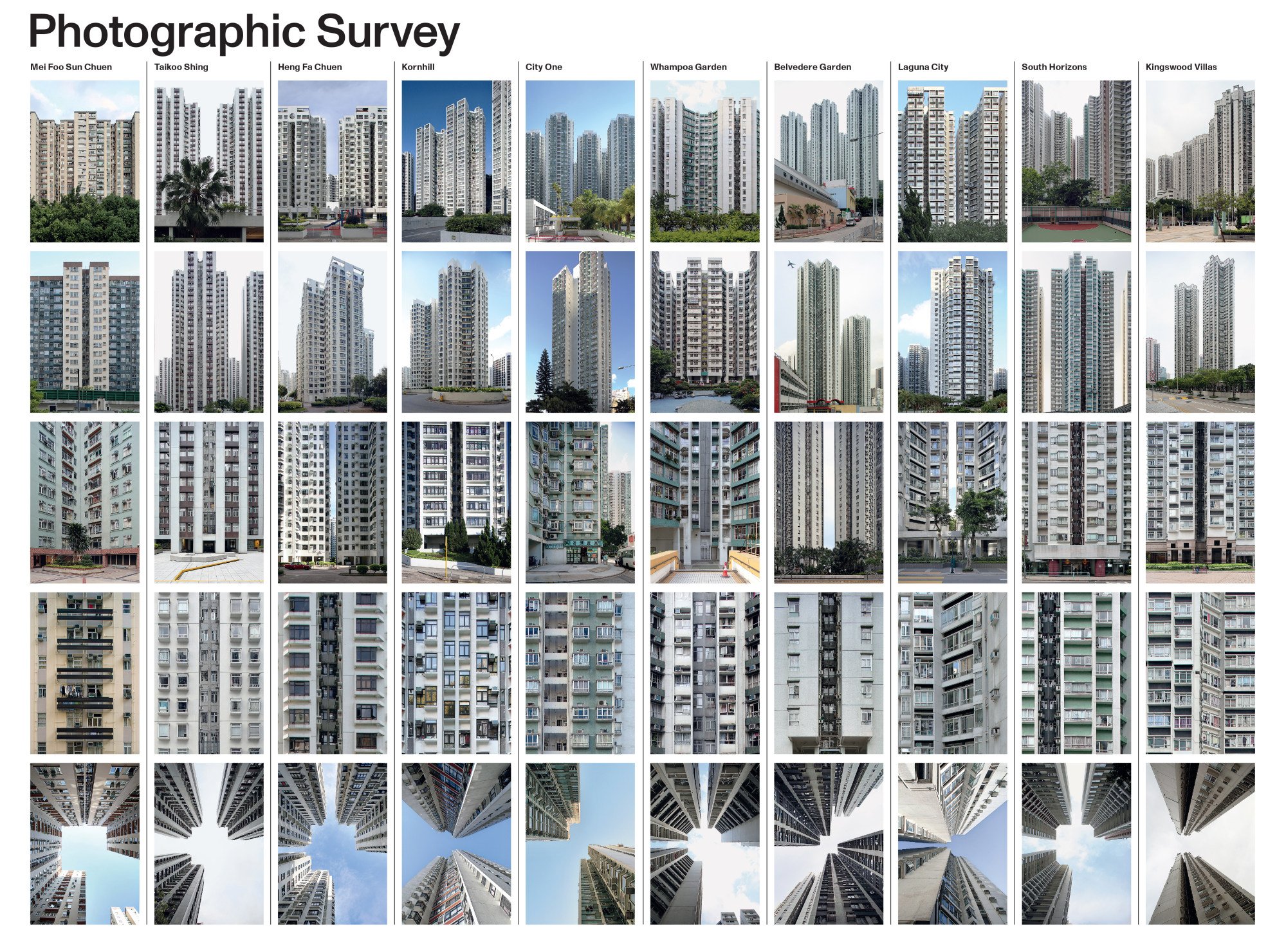

(2012) – a cityscape showing uniterrupted rows of estate towers that seemed to have no beginning or end – was a worldwide success. Although their monotonous visual appearance is sometimes criticized for being soulless, approximately one million people reside in Hong Kong’s 100 largest private residential estates. When you look closely, these developments may be more fascinating than they initially seem.

Our new platform featuring carefully selected content with detailed explanations, frequently asked questions, in-depth analyses, and eye-catching visual aids, all brought to you by our team of highly skilled professionals who have received numerous awards for their work.

Carmel Carlow and Beth Lange met while they were both teaching at the University of Hong Kong’s Faculty of Architecture; Lange remains there at present while Carlow has subsequently relocated to the American University of Sharjah, which is situated near Dubai.

We were both interested in software technologies that enable students and professors to easily modify building form and shape,” says Carlow. This implies that buildings can be designed and constructed in a production-line manner, with standardized forms and components. Their exploration of standardization led them to Hong Kong’s prevalent housing estates. “I was both intrigued and astonished by the striking similarity of buildings in Hong Kong,” says Lange. “It’s truly remarkable.

They also found that, despite extensive research into the history and structure of Hong Kong’s public housing estates – which are home to over half the population – there has been surprisingly little exploration of private estates built by large property companies. “They had not been thoroughly researched or documented,” says Lange.

A comprehensive analysis of this estate, established in 1989 and comprising five towers and 4,016 residents, has been conducted. Specifically, the researchers have also studied ten estates, built between the 1960s and 1990s, which showcase different generations of design and construction methods. “These developments are essentially a reflection of their respective eras,” notes architect Lange.

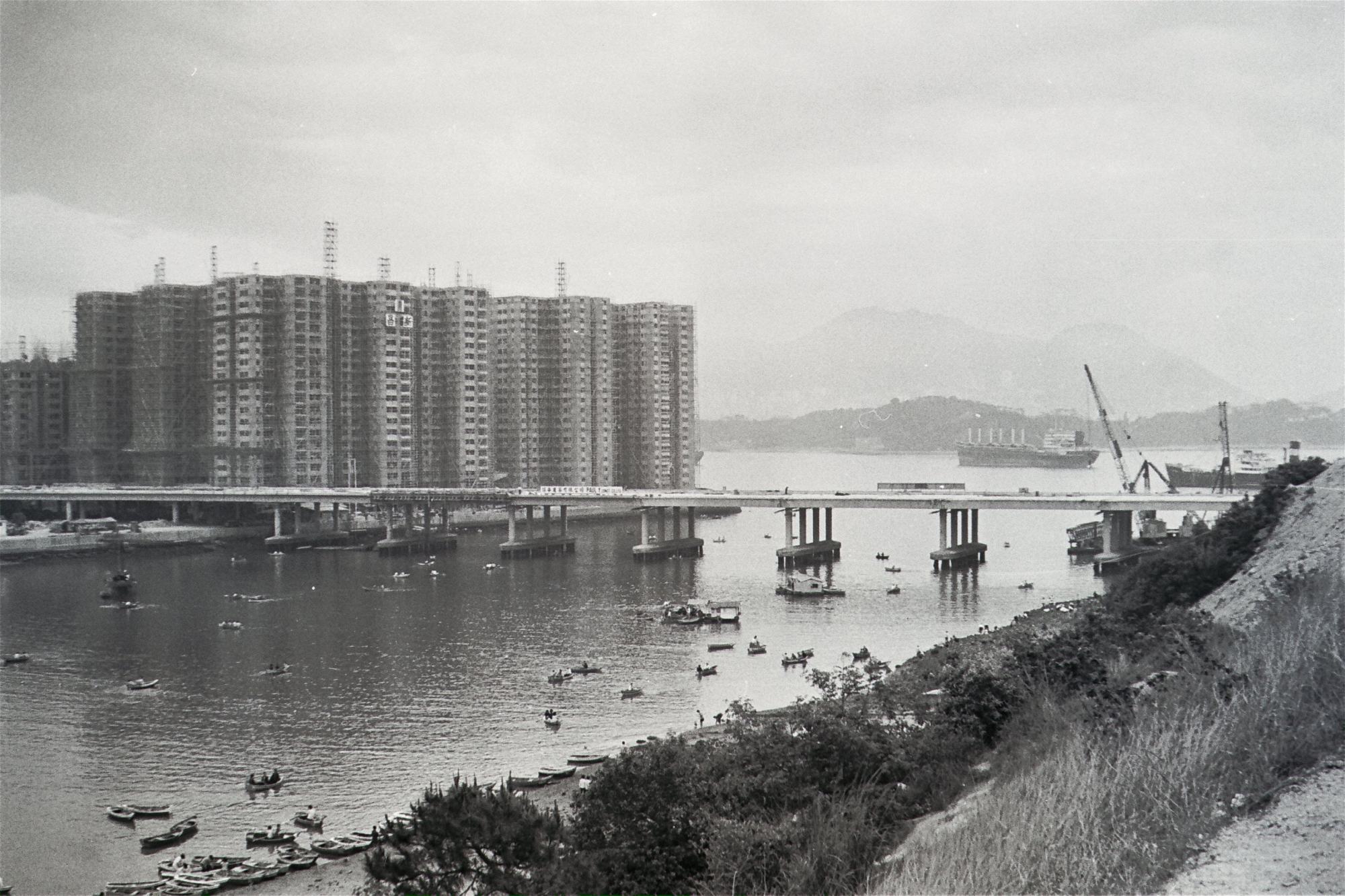

That development began with Mei Foo Sun Chuen, Hong Kong’s first large-scale private housing project, which broke ground in 1968 and was finished 10 years later, on the site of the former Mobil oil depot in Kowloon. Until then, housing estates had been built primarily by the government to rehouse squatters whose homes had been destroyed by fire or landslides. Mei Foo was the first time an estate targeted members of Hong Kong’s increasingly expanding middle class. A total of 99 towers, each 20 storeys tall, were built atop a garden podium with shops, wet markets and community facilities underneath. When the estate was completed, it was home to 80,000 people, although today the population is a little under half that, as families have shrunk in size.

Mei Foo was – and still is – a highly sought-after location for residents. Its success served as a model for numerous subsequent estates, which mirrored its design by arranging towers on either side of shared facilities. Although they are now a defining feature of Hong Kong’s skyline, they borrowed a concept from elsewhere: their roots date back to the early 1920s, when Swiss architect Le Corbusier conceived city plans to accommodate large numbers of people in separate, standardised blocks of buildings laid out in an orderly manner. This urban design philosophy later influenced the creation of Stuyvesant Town, a large middle-class housing development built in the 1940s to replace an old working-class neighborhood on Manhattan’s Lower East Side. As a desirable place to live, Stuyvesant Town still offers its residents a convenient location, community events, ample green space, and relatively affordable rents.

Estates similar to these were constructed globally, but in hardly any cities did they become as deeply ingrained as in Hong Kong, whose unique conjunction of a rapidly growing population coupled with exceptionally cramped geography led to increasingly crowded urban development.

While most Hong Kong residents live in high-rise developments, the notion of high-density living doesn’t carry the same negative connotations as it does in other parts of the world,” says Carlow. “Many of the estates we examined are quite upscale, with amenities like clubhouses that help mask the fact that high-rise buildings are often directly mirrored next to one another. Hong Kong residents are accustomed to this type of living arrangement.

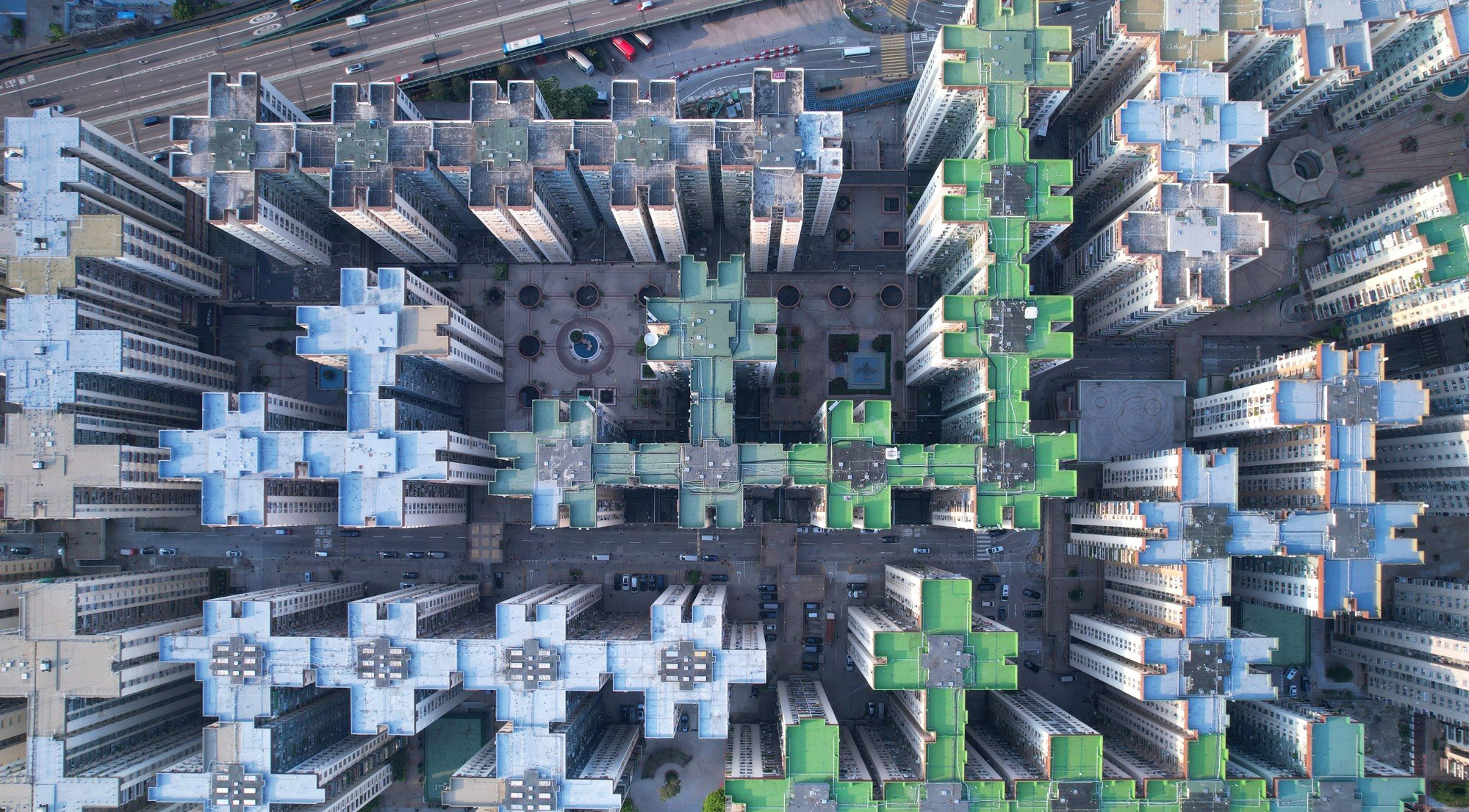

What catches one’s eye, though, is just how repetitive most of these estates are. That was once a quality associated with public housing estates, whose goal was to accommodate as many people as affordably possible. But in recent years, the Hong Kong Housing Authority has adopted a site-specific approach for new development, which means the latest generation of public housing estates are each designed in response to the landscape around it, with more variety in building and flat types than ever before. By contrast, private estates have become progressively more standardized.

When they studied the structure of Mei Foo’s seemingly identical buildings, Lange and Carlow were surprised to discover that it actually holds the most mix of types among all private housing estates they studied. “There’s a great deal of individuality within that estate, which you don’t notice at first view,” says Lange. There are 223 distinct unit types in Mei Foo, and 68 of its 99 towers have a unique layout. In comparison, Kingswood Villas has just 15 types of units, and 56 of its 58 towers are exact replicas of one another. Almost all of its flats have the same peculiarly shaped living room – like a rectangle attached to a trapezoid – with a narrow hallway lined by a kitchen, bathroom, and bedrooms.

teams of rooms and then tenements, ultimately followed by a block of towers whose bay windows and tile-covered facades are all incredibly uniform.

This was mainly done to save costs and time: land has always been expensive in Hong Kong, so developers try to cut costs wherever possible. They achieve this by adhering strictly to the minimum standards set by Hong Kong’s building code. The code is not static, and it’s updated regularly in response to various factors like fire safety, environmental issues, and technological advancements. For example, the code mandates windows in every room, prompting architects to design cross-shaped tower blocks that comply with this requirement while allowing for a higher number of apartments per floor.

There are also certain characteristics that allow developers to receive a gross floor area exemption – essentially, additional saleable space in exchange for providing a feature that Hong Kong’s planners deem serves the public good. A notable example is the bay window, which was introduced in the 80s to bring more natural light into apartments.

“Once it had been integrated into the system, it became a widespread practice,” says Lange.

Carlow notes that many innovative developments in this area are often driven by developers and their in-house architects, who must strike a balance between extreme density, profit, and livability. While nearly all the estates featured in the book are variations on the basic cruciform design pioneered by Mei Foo, designers have carved out nooks and recesses, or “re-entrants” as they are technically known, to accommodate additional service rooms and bathrooms that can breathe fresh air as required by law. Many of the estate flats have a diagonal exterior wall in the living room, which Carlow says serves as a way to direct the living room’s view away from neighboring high-rise buildings rather than being a code-compliance requirement.

A prominent trend observed in the design of private housing estate apartments is that available living spaces are continually decreasing, having plummeted from a minimum of 387 square feet in the 1980s to only 170 square feet in the present day. Simultaneously, layouts have become increasingly standardized, with more rigid restrictions being imposed on what residents are permitted to do with these confined spaces.

Most internal walls in new apartments are structural, a cost-effective way to support a building that could be up to 70 stories tall. According to Chan, “altering these walls can be complicated and expensive, which means every single family will have similar layouts.”

When a significant number of housing options are restricted on a large scale, the risk arises of diminishing the variety and diversity within an estate or neighborhood,” says Carlow. “You can only cater to very narrow segments of society when everyone is confined to the same style of residential unit.

The layout of some of these estates can be problematic. Estates built in the 1970s and 1980s, like Mei Foo, City One, Whampoa Garden, and Taikoo Shing, are structured more like traditional villages with a mix of public streets, plazas, and shopping areas. However, during the 1990s, the design changed to estates placed on top of a single, enclosed mall. Frequently, residents have to go through the mall to get to the lift lobby that leads to the podium level, where they can access their specific residential towers.

“Neighbourhoods have lost their essence,” says architect and urbanist Christopher Law Kin-chung. In his opinion, traditional street-based communities have a unique dynamic and flexibility that modern estates with centralised shopping malls lack.

A sense of loneliness,” former Tseung Kwan O resident Maria Luk told the South China Morning Post in a 2020 profile of her neighborhood. “We rarely saw our neighbors during the 10 years we lived there. I wouldn’t even recognize their faces in the elevator, but we became close with the security guards and cleaning staff.

Despite the availability of other housing options, private estates continue to be in demand. “I was looking for a place that was very convenient, particularly close to the MTR station, and a larger estate so I could make the most of the public amenities available”, says journalist Kimberley Tsang, who resides in Metro City, situated near the Po Lam MTR station in Tseung Kwan O. While she has some minor criticisms about the layout of her flat; she notes that the kitchen and main bedroom could be more spacious, even if it meant a smaller second bedroom. However, she appreciates the proximity to amenities, the clubhouse facilities, and the feng shui garden shared by residents. “Our gardener does a phenomenal job,” she says.

Chan says many of his clients purchase flats in housing estates because of the shared facilities – which can encompass swimming pools and gyms, as well as tennis courts, cinemas, karaoke rooms, and barbecue areas – and the management, which is viewed as being proactive compared to stand-alone buildings. “People buy in large estates to have fewer headaches,” he says.

There is no leadership. You end up with rodents.

He decided to move back to Kornhill to raise his family. “Now that I have kids, I find the amenities to be super useful,” he says. “Every day around 3pm, all the kids gather with the domestic helpers and the mothers who don’t need to work. They bring their own toys, they hang out until around 5 or 6 o’clock and then leave for dinner.”

Tsang and Chan also point out that while the 80s-era estates where they live have unique characteristics, not all estates built in this period are created equal.

They had initially planned to adopt a more critical approach. “We were treating the project as a critique of the estates in their standardization and uniformity,” Carlow says. However, as they delved deeper into the matter, they discovered that every estate has its own unique characteristics, even if they seem minor. Ultimately, they found that they are a successful way to provide comfortable housing for a large population in a limited space.

Recognizing this building style is just a part of Hong Kong’s history,” Carlow notes. “I previously characterized Hong Kong as an incredibly impressive city boasting numerous ordinary buildings,” he says. “However, having relocated to Dubai where every structure strives to make a statement, my perspective has shifted.” He now appreciates “the consistency and standardization found in Hong Kong, which is a defining characteristic of its distinct identity.

More Articles from SCMP

There has been a release by the Mainland China involving a Taiwanese fishing boat and its skipper who were retained near Quemoy in July.

A 93-year-old woman in Hong Kong was fatally struck by a rubbish truck that was reversing. The driver of the vehicle has been taken into custody.

Former CIA Director says Donald Trump wants to achieve peace with China “through US strength”.

**SCMP Best Bets: Punters Can Get Off to a Blazing Start at Sha Tin**

This article was originally published on the South China Morning Post (www.scmp.com), a prominent English-language news outlet covering China and Asia.

This is a request for a specific task, but the “text” is a copyright information which cannot be processed, as it does not convey meaningful content. However, I can assume you meant to provide an actual text from the South China Morning Post. If you provide the text, I’ll be happy to paraphrase it in plain English for you.